“Far Beyond the Stars”

Written by Marc Scott Zicree and Ira Steven Behr & Hans Beimler

Directed by Avery Brooks

Season 6, Episode 13

Production episode 40510-538

Original air date: February 11, 1998

Stardate: unknown

Station log: Kira reports to Sisko that the Defiant has found no sign of the Cortez, lost while patrolling the Cardassian border. The captain was an old friend of Sisko’s, which makes him less than enthusiastic about his father Joseph visiting the station. Sisko doesn’t know how much more he can take, how many more friends he can lose. Joseph tries to comfort him, then goes off for a dinner date with Jake. Sisko talks with Yates, failing to convince her to cut back on her cargo runs for fear of Jem’Hadar attack.

Sisko also sees a man in a suit and hat and glasses (who looks a lot like Odo), as well as a man in a New York Giants baseball uniform (who looks a lot like Worf), but nobody else sees them. He follows the latter into a cabin, only to find himself on a street in 1953 New York City, where he promptly is hit by a cab. He wakes up in the infirmary, surrounded by Yates, Joseph, and Jake. Bashir says he’s got odd synaptic patterns, similar to what he experienced when the wormhole aliens gave him visions of Bajor.

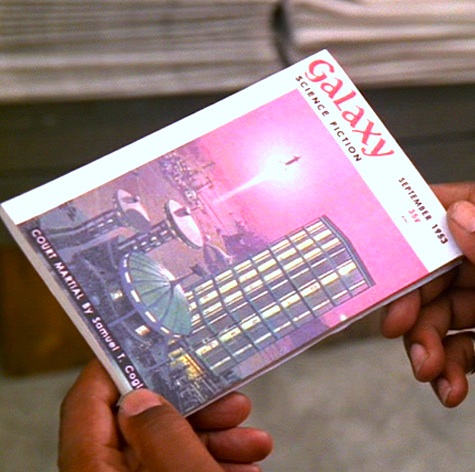

And then Sisko’s back in New York, buying a copy of Galaxy Magazine from a news vendor (who looks a lot like Nog), and Sisko himself is wearing glasses, a suit, and a hat. His name is Benny Russell, and he meets up with Albert Macklin (who looks a lot like O’Brien) on the way to the office. Both of them are staff writers for the science fiction magazine Incredible Tales.

They arrive at work, where writer Herbert Rossoff (who looks a lot like Quark) and editor Douglas Pabst (the one whom Sisko saw earlier) are arguing over donuts, the latest in a series of arguments between those two. The husband-and-wife team of Kay and Julius Eaton (the former writes as K.C. Hunter to hide her gender) observe and make amused commentary. Once that’s over, and Pabst keeps Rossoff from quitting (again), artist Roy Ritterhouse (who looks a lot like Martok) comes in with some illustrations, which each of the writers takes as their assignment for the next issue’s story.

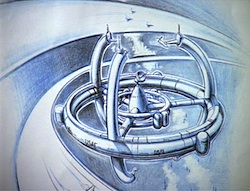

One of Ritterhouse’s drawings looks a lot like Deep Space 9. Russell is utterly captivated by the image and he takes it.

Pabst also says that their readers want pictures of the authors, and he also says that Kay and Russell can sleep late that day. Kay bitterly complains that heaven forfend anyone know that a woman is writing, and a Negro doing likewise would be just as bad from the publisher’s perspective. Russell angrily cites several Negro writers who are publicly known to be black—W.E.B. DuBois, Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, Ralph Ellison, and Zora Neale Hurston (who’s also female)—but Pabst says those guys write for liberals and intellectuals. The readers of Incredible Tales want to know that their writers are “as white as they are.” Rossoff is the most vocally disgusted, but everyone’s pretty displeased about it.

On his way home, Russell is harassed by two detectives, Burt Ryan (who looks a lot like Dukat) and Kevin Mulkahey (who looks a lot like Weyoun), who assume that he works as a janitor or something. When he comes out of the subway in Harlem, he passes a preacher (who looks a lot like Joseph) who talks to Russell directly and mentions the Prophets several times amidst his Bible thumping.

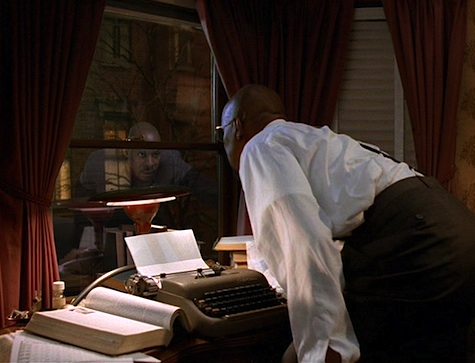

Sitting at his typewriter in his small apartment, Russell starts to write his story, which stars Captain Benjamin Sisko. At one point, he sees his reflection in his window—but his reflection is Sisko…

The next morning he goes to a diner for breakfast, where he’s served by his fiancée, Cassie (who looks a lot like Yates). The owner is thinking of retiring in the next few years, and she might be willing to sell to Cassie and Russell. Russell is reluctant—he’s a writer, not a diner owner, but Cassie doesn’t see that as sufficiently lucrative.

Their discussion is interrupted by the arrival of the baseball player from earlier, Willie Hawkins. He and Russell have a semi-friendly rivalry going over Cassie, though Cassie makes it clear that her heart belongs to Russell.

Hawkins then goes to greet his adoring public (smitten women and kids who want autographs), and Russell is joined by Jimmy (who looks a lot like Jake). He tries to sell Russell a watch that he “found.”

Everyone in the Incredible Tales office reads Russell’s story, called “Deep Space Nine,” and everyone loves it, even the new secretary Darlene Kursky (who looks a lot like Dax). Kay says she really likes the Major Kira character—a real “tough cookie”—and Russell briefly sees her as Kira. However, Pabst says he can’t print a story with a Negro captain. Rossoff and Russell are both livid, but Pabst insists he’s not a crusader, he’s not trying to change the world, he’s an editor of a magazine who answers to a publisher and distributors, and they can’t handle a Negro captain. Pabst will only print it if he changes the protagonist to a white guy. By way of apology, Pabst assigns him a novella that he’ll put on the cover.

Russell drowns his sorrows at the diner. Jimmy says he knew that colored people in space would never fly. “Only reason they’ll ever let us in space is if they need someone to shine they shoes.” Cassie, meanwhile, thinks this may be God’s way of saying he should give up writing and go into the restaurant business. When Hawkins puts a hand on his shoulder and asks if he heard the game last night, Russell sees Worf in full Klingon armor, and it scares the crap out of him.

Again, Russell meets the preacher, who urges him to walk in the path of the Prophets. He goes home and writes more stories about Captain Benjamin Sisko, colored captain. He forgets all about his date with Cassie, and she shows up at his apartment around midnight. They dance a bit—but as they dance, they’re in Sisko’s quarters on DS9 and Cassie looks like Yates.

Pabst is livid when Russell shows up with, not the novella he was assigned, but six more Ben Sisko stories, after he refused to publish the first one. Julius suggests printing them all with a private publisher, a boutique edition of 50-100 copies. Kay points out that writing it in chalk on the sidewalk would garner a bigger audience. Macklin then suggests making it a dream, and Kay jumps on that, saying it can be a shoe-shine boy or a convict, someone dreaming of a better future. Rossoff thinks that it guts the story, but Julius thinks it’ll be more poignant. Russell agrees to make that change, saying that it’s better than chalk on the sidewalk, and Pabst is then willing to publish it.

A happy Russell bumps into Jimmy on the street, but he’s distracted, not even taking Russell up on his offer to buy him lunch. Undaunted, Russell goes to the diner and interrupts Hawkins’s latest attempt to impress Cassie with his hitting prowess by saying that they bought the story, and at three cents a word. He takes her out to the Rendezvous Club, where they dance the night away and he sings to her.

On their way home, they encounter the preacher, who cautions that joy and despair go hand in hand, and he also grabs Russell’s ear the same way Bajoran clerics do.

Then they hear gunshots. Jimmy’s been shot dead by Ryan and Mulkahey, allegedly for breaking into a car. When Russell expresses displeasure at his friend being shot for so minor a crime, he gets the crap kicked out of him for his trouble. During the beating Ryan becomes Dukat and Mulkahey becomes Weyoun.

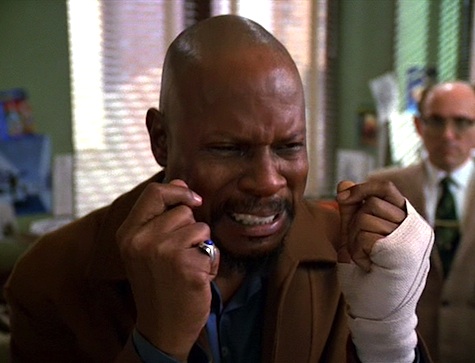

Weeks later, Russell is finally well enough to go into the office, which is good, as this is the day the issue of Incredible Tales with “Deep Space Nine” is due back from the printer. He limps into the office with a cane, and learns that Macklin has sold a novel to Gnome Press. The celebration about that is short-lived when Pabst arrives without a magazine. Mr. Stone, the publisher, had the entire run pulped because it “didn’t live up to the high standards,” which is code for “we can’t print a magazine with a colored hero.” To add insult to injury, Stone has instructed Pabst to fire Russell.

That’s the straw that breaks his back. Russell has a complete mental breakdown, and he’s taken away by doctors.

In the ambulance, he is wearing Sisko’s uniform, but still has his glasses and watch on. The preacher is in the ambulance, telling him that he is the dreamer and the dreamed.

And then Sisko wakes up in the infirmary, having been unconscious for only a few minutes, but the synaptic issues are all gone, to Bashir’s confusion.

Later, Joseph visits Sisko in his quarters. Sisko has decided to stay the course, to keep fighting, even if it’s hopeless. He also wonders if Russell was real and he’s the figment of a writer’s imagination.

The last image is of Sisko looking out the window of his cabin, seeing the reflection of Benny Russell.

The Sisko is of Bajor: Russell has only been writing professionally for a few years. Prior to that, he was in the Navy. He also wrote things there (and based on the tie-in fiction, also wrote some radio scripts when he was younger), but he dismisses what he wrote then to Cassie as “amateur.”

Don’t ask my opinion next time: Kay has to write as K.C. Hunter, a common practice among female genre writers to avoid letting people know their sex. Others who did this were C.L. Moore and original series screenwriter D.C. Fontana (not to mention Star Trek novelists A.C. Crispin and J.M. Dillard). She’s also the one who fights most passionately for Russell’s stories to be printed. (Rossoff is louder and more obnoxious about it, but the character is naturally combative and resentful of authority. Kay’s passion is a bit more legitimate.)

The slug in your belly: Darlene thinks the woman with the worm in her belly is “gross—but interestin’!”

There is no honor in being pummeled: At one point, Cassie asks Hawkins why he continues to live uptown, but Hawkins bitterly says that the white players barely tolerate playing with him—living with them is a step too far. Besides, in Harlem, he’s a star; in a white neighborhood, he’s just some colored boy who can hit a curveball. It’s the only time the struttin’ Hawkins is at all bitter.

Preservation of mass and energy is for wimps: Pabst tries very hard to balance the needs of the magazine versus the needs of his writers, and doesn’t always succeed. While it’s to his detriment that he rejects “Deep Space Nine” initially, he does allow the others to talk him into it as a dream story, even giving Russell a higher word rate. But in the end, he has to do what his boss tells him to do.

Rules of Acquisition: Rossoff is a loudmouth and an agitator, for all that he’s pretty much right about everything he says. He’s dismissive of Macklin and Julius’s talents, disdainful of Kay’s story choices, and is constantly crawling up Pabst’s ass. When Pabst accuses him of being a Communist (by saying he’s “been angry ever since the day Josef Stalin died”), a very serious and dangerous insult in 1953, Rossoff tries to physically assault Pabst.

No sex, please, we’re Starfleet: Hawkins is very much a player, constantly hitting on Cassie despite her multiple rejections. When Russell leaves the diner saying he’ll pick Cassie up at ten, Hawkins immediately asks what she’s doing until ten. “Whatever it is,” she replies tartly, “I won’t be doing it with you.”

Keep your ears open: “If the world’s not ready for a woman writer, imagine what would happen if it learned about a Negro with a typewriter. Run for the hills! It’s the end of civilization!”

Rossoff’s sarcastic reply to Pabst saying that Russell and Kay’s pictures won’t accompany their stories.

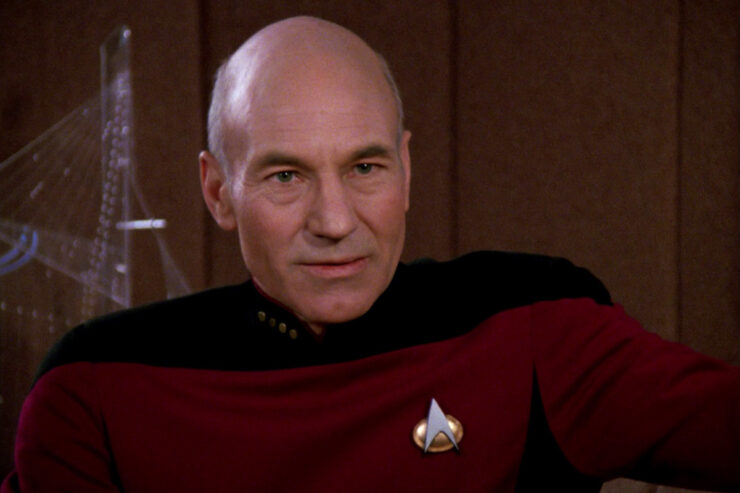

Welcome aboard: Many of the show’s recurring regulars appear, albeit not as themselves (except briefly in flashes in some cases): Marc Alaimo and Jeffrey Combs play Ryan and Mulkahey, Aron Eisenberg plays the news vendor, and J.G. Hertzler plays Ritterhouse. Penny Johnson and Brock Peters also appear, both doing double duty, the former as both Yates and Cassie, the latter as both Joseph and the preacher.

The regulars all play roles in the 1950s setting as well. In the case of Rene Auberjonois, Armin Shimerman, and Colm Meaney, they only appear as Pabst, Rossoff, and Macklin, with Odo, Quark, and O’Brien not appearing at all in the episode. Avery Brooks doubles as Russell, Nana Visitor as Kay, Alexander Siddig as Julius, Michael Dorn as Hawkins, Terry Farrell as Darlene, and Cirroc Lofton as Jimmy.

Trivial matters: Incredible Tales was based on other magazines of the era that published science fiction, two of which, Galaxy Magazine and Astounding Science Fiction, are mentioned by name. The various folks at the magazine are all at least loosely based on real-life SF writers: Russell on Samuel R. Delany, Rossoff on Harlan Ellison, the Eatons on Henry Kuttner and Catherine Moore (a.k.a. “C.L. Moore”), and Macklin on Isaac Asimov (even selling his first novel about robots to Gnome Press just as Asimov sold I, Robot to that publisher). Pabst is at least partly modelled on John W. Campbell, one of the most influential editors and magazine publishers (and authors) in the field. In addition, Hawkins was inspired by Willie Mays, who was a hot young superstar center fielder for the New York Giants in 1953. (Well, actually, Mays missed the 1953 season because he was serving in the military, fighting in the Korean War, but still…) Russell’s bitter query of Hawkins as to why the Giants were mired in fifth place is accurate, as that was where the Giants finished that year.

Avery Brooks has often cited this as his favorite episode, and it was his choice for the Star Trek Fan Collective: Captain’s Log collection.

The covers for Galaxy, Astounding, and Incredible Tales that were seen use matte paintings from the original series: respectively, Starbase 11 from “Court Martial” (and the issue has a story in it with that title, written by “Samuel L. Cogley,” the name of Kirk’s lawyer from that episode), Eminiar VII from “A Taste of Armageddon,” and Delta Vega from “Where No Man Has Gone Before.” The stories in Incredible Tales are all original series references: “The Cage” by “E.W. Roddenberry,” listed as the author of Questor and billed as the first of a new series (it was the original pilot…); plus “The Corbomite Maneuver” by Jerry Sohl (with illustrations by Matt Jefferies), “Journey to Babel” by D.C. Fontana, “Where No Man Has Gone Before” by Samuel Peeples, and “Metamorphosis” by Gene L. Coon.

This is the only time in any of their many Star Trek appearances that Michael Dorn, Jeffrey Combs, Aron Eisenberg, J.G. Hertzler, and Armin Shimerman appear without any makeup or prosthetics. It’s only the second time (after “Time’s Arrow”) where Marc Alaimo so appears.

Casey Biggs was supposed to appear in this episode, but was working in New York and couldn’t get away. He will appear when the show revisits Russell in “Shadows and Symbols” at the top of season 7.

The “Trill Building” is a double joke, a play on both Dax’s species name and the famous Brill Building in Times Square in New York.

This episode aired in February, which is Black History Month. This was not intentional, simply a happy coincidence.

The music playing during Russell’s argument with the news vendor is “The Glow-Worm” by the Mills Brothers. After they leave the Rendezvous Club, Russell sings a bit of “Everything I Have is Yours” to Cassie.

One of the times when Rossoff is threatening to quit and packing the items on his desk, he packs an actual Hugo Award. The awards, named after Hugo Gernsback, the founder of Amazing Stories, the first magazine dedicated to “scientifiction,” in 1928, were in fact first awarded in 1953, and Star Trek has won four for Best Dramatic Presentation (“The Menagerie” two-parter, “City on the Edge of Forever,” “The Inner Light,” and “All Good Things…”). However, the actual award used was one of the two that Rick Sternbach won for Best Professional Artist in the late 1970s.

Also on Rossoff’s desk is a memo from Pabst saying that no one would believe that a cheerleader could kill vampires, a reference to Buffy the Vampire Slayer, on which Armin Shimerman had a recurring role as Principal Snyder.

The poster outside the Rendezvous Club advertises “Phineas Tarbolde and the Nightingale Women,” the latest in a series of references to the poem quoted by Gary Mitchell in “Where No Man Has Gone Before.”

This episode was novelized by Steven Barnes, who expanded considerably on Russell’s story (with portions taking place in 1940 as well), and also wrote an excellent afterword about the roles of African Americans in genre television and movies. The novel’s cover was in the style of the Incredible Tales covers, using the artwork seen in the episode designed by Ritterhouse to illustrate Russell’s “Deep Space Nine” story, as well as listings of other stories written by the characters seen in the episode (as well as one by “M.S. Zicree,” after Marc Scott Zicree, whose story this episode was based on). It was the last mid-season Trek episode to receive the novelization treatment, as all further novelizations were of season premieres and season enders (sometimes both at the same time, as with Enterprise’s “Shockwave”), as well as movies.

Besides the followup in “Shadows and Symbols,” Russell’s story is continued in various stories and novels, including Unity by S.D. Perry, Warpath by David Mack, Plagues of Night and Raise the Dawn by David R. George III, and most notably in the brilliant “Isolation Ward 4” by Kevin G. Summers in Strange New Worlds IV. In addition, a younger Russell is seen in George’s Provenance of Shadows, “Captain Proton and the Orb of Bajor” by Jonathan Bridge in SNW4 (as the author of a Captain Proton radio play from 1938, using the holodeck program favored by Paris and Kim on Voyager), “When the Stars Come a-Callin’” by Ben Raab & John Lucas in WildStorm’s Star Trek Special graphic novel (a prequel to this episode, showing how Russell came to work for Incredible Tales), and, most amusingly, in Captain Proton: Defender of the Earth, a short novel by D.W. “Prof” Smith (really Dean Wesley Smith), which was presented as a magazine from the early 1930s, complete with a letters page, which included a letter from a teenager named Benny Russell who said he’d some day write stories like the Captain Proton ones himself.

Bashir notes that Sisko’s synaptic patterns are the same as they were when he was receiving visions in “Rapture.” Yates immediately asks if he needs surgery again, as he did in that episode.

Walk with the Prophets: “Benny Russell is dreaming of us.” It’s very easy to forget now how radical Star Trek was in 1966.

At the time the show went on the air, people were watching news stories about a war being fought against people who looked like Mr. Sulu, and civil rights unrest from people who looked like Lieutenant Uhura, and we were all living in fear of being bombed into oblivion by people who sounded like Mr. Chekov. Yet there, in a depiction of the future, we had an Asian guy, a black woman, and a Russian man all working happily alongside the white folks (not to mention the pointy-eared alien). More to the point, though, nobody drew attention to it. The only one of the three whose heritage was a factor was Chekov, and then only for a running gag about how Russians “inwented” everything, something not considered important by anyone else. We knew Sulu loved botany and fencing and firearms, we knew Uhura loved music, but those were considered more important than even mentioning their race.

DS9 was as important in its own way by having an African-American lead, not to mention an Arab supporting character. Again, that fact wasn’t important, and up until this episode is never brought up in the case of either character. (The closest we came was casting an Arab-American activist as Bashir’s mother.) Sisko’s engineering background and love of cooking is more important than the color of his skin in the 24th century.

Back around 2000 or so, Pocket Books editor John Ordover decided to try an experiment. There had been some online interest from some readers about a Captain Sulu novel, picking up on Star Trek VI establishing that Sulu was in command of the Excelsior, and John wanted to see how widespread that interest was (especially given the poor sales on a previous Sulu solo novel, The Captain’s Daughter by Peter David). He called for a letter-writing campaign for people to write physical letters requesting a Captain Sulu novel, and if he got enough, he’d do it.

As it happens, he didn’t reach the stated goal, although another editor, Marco Palmieri, was more than happy to do two Captain Sulu novels (both by Andy Mangels & Michael A. Martin, the Lost Era novel The Sundered and the Excelsior novel Forged in Fire) in 2003 and 2007 without anybody writing any letters. But I was given the opportunity to read some of the letters that people sent, and I was blown away. The importance of the Uhura character has gotten plenty of press, from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. famously asking her not to quit the show because of how important her being there was, to the litany of black women from Whoopi Goldberg to Dr. Mae Jemison who cited Uhura as a major influence on their lives. In contrast, Sulu doesn’t get anywhere near the same press, but to Asian Americans he was just as important a symbol as Uhura was to African Americans.

And, as Steven Barnes eloquently stated in the afterword to his mostly brilliant novelization of this episode, Sisko is a hugely important symbol for African Americans, an even bigger step than Uhura, because black folks don’t get to be the lead nearly often enough. Just look at other successful genre shows of the past two decades: Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., Angel, Arrow, Babylon 5, Battlestar Galactica, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Continuum, Eureka, Farscape, Hercules, Lost Girl, Stargate SG-1/Atlantis/Universe, Warehouse 13, Xena, The X-Files, to name but a few that spring to the top of my head—plus, of course, the other three Star Trek spinoffs. In each and every one of those, the primary lead is white, except for Galactica where he’s played by the Latino Edward James Olmos (though his son is played by the incredibly white Jamie Bamber, just to confuse the issue). African Americans can be the sidekicks, the secondary leads, the clever advisors, the muscle—but Sisko stands out as a lead.

People who make television shows are still just as scared as Douglas Pabst.

And that’s why this episode is important. We see so many aspects of how far humanity has to go to get to the egalitarian 24th century. The era picked was a good one. It predates the ugliness of Civil Rights unrest (not to mention the antiwar movement) of the 1960s and 1970s, but postdates things like a woman’s right to vote, the integration of the armed forces, and the integration of sports. It’s an era where progress is evident, but it hasn’t progressed nearly far enough. Yes, Willie Hawkins can play for a major-league team, but that’s only been the case for six years, and he still can’t really leave his neighborhood. Russell and Kay can write for Incredible Tales, but they can’t have their picture next to their stories.

I particularly like how they don’t lose sight of the fact that it isn’t just racism that’s an issue. We’ve got the sexism that makes it necessary for ”K.C. Hunter“ to be Kay’s byline, we’ve got the fear-mongering of Pabst red-baiting Rossoff, we’ve got the utter brutality of Ryan and Mulkahey, who obviously receive no reprimands for their actions. Hell, the only person who even says anything when they assault Russell is Cassie.

(The only real flaw in Barnes’s novelization is his dismissal of Kay’s objection to not having her picture in the magazine: “What was a matter of ego for Kay was survival for Benny.” That seriously trivializes sexism, forgetting, among other things, that Kay was part of the first generation of women who were born with the right to vote, women having only been granted that right a scant 33 years previous.)

Russell bitterly says that wishing never changed anything, but he’s wrong (as he sorta-kinda learns at the end). The dreams of people like Russell, like Gene Roddenberry coming up with his multicultural bridge, like Nichelle Nichols sticking with a role that may not have been fulfilling, but which fulfilled something bigger, like Brandon Tartikoff at Paramount green-lighting a genre show with a black lead, something that has been vanishingly rare even now, are what are important and what will help effect change.

One other thing about this episode I want to mention is that, as a writer, I adore the scene where everyone bats ideas around, trying to make “Deep Space Nine” work as a story that Pabst can actually accept. It’s a fairly accurate rendition of your average writers’ gab session, throwing ideas around and trying to figure out ways to make a story work better. In an episode that gets so much right already—the fashions, the cars, the attitudes, the accents—that scene stands out in particular.

The acting in the episode is beyond superb. I still wince a bit when Russell has his breakdown, as Avery Brooks tends to overplay that stuff, but aside from that, it’s great. In particular Armin Shimerman, Cirroc Lofton, Rene Auberjonois, and Michael Dorn stand out, creating complex characters that they inhabit superbly—and final scene notwithstanding, so does Brooks. Plus, it’s always a joy when you put Brooks together with Brock Peters in a scene.

The 24th-century stuff is a bit weak. The lesson that Sisko must soldier on even in the face of awfulness is a bit sledgehammery, and the preacher’s mixing of Bajoran and Christian theology is unintentionally hilarious, but these are minor nits. This is one of Trek’s finest hours, reminding us not just of how far we can go, as Trek usually does, but of how we can get there.

Warp factor rating: 10

Keith R.A. DeCandido’s newest novel is Sleepy Hollow: Children of the Revolution, based on the FOX show that just started its second season, which you can preorder from Sleepy Reads or find in your local bookstore.

Excellent review! This is probably your best writing in all the rewatch articles (so far). Nicely sums up what this episode and Trek are all about.

Cheers!

I loved this episode, it was different from standard of Star Trek episodes at the time. The English teacher I had for 11th grade showed this episode to show how SCIFI is important to American Literature

*standing ovation*

For this episode and your review.

‘Nuff said.

Great review Keith.

I haven’t seen this episode in years, but it was nice to be reminded of it through this post. Thanks for showing the real-life parallels (even if loosely based) of each of the folks at the magazine.

This is a terrific Twilight Zone-y sort of reality-bending episode and a terrific commentary on racism and all that… but the premise makes no sense to me in the context of Deep Space Nine. Why would the Prophets send him a vision so totally unlike anything we’ve ever seen from them before, why would it be about a 1950s science fiction writer, and why would they hope to inspire him with a vision whose lesson is “You’re doomed to failure and your reality might not even exist anyway”? The whole thing feels like they compromised the internal consistency of the story in order to shoehorn in a tale — however terrific — that just doesn’t fit in the DS9 narrative.

But then — spoiler alert — the second Benny Russell vision in the seventh-season opening 2-parter is a trick by the Pah-wraiths to make Sisko lose hope. So I suspect the same was true of this one. They were trying to get him to either give up, doubt the nature of his reality, or both, but they failed. That’s the only explanation that makes sense to me in-universe.

My favorite DS9 episode! Excellent review.

Of the many nods and mentions in the episode, you forgot the very obvious model in the middle of the table: the rocket Tintin and the gang used to go to the moon in Objectif Lune (1953) and On a marché sur la Lune (1954), by Hergé. Incidently, the former story was published as a collected album the same year the episode is set in.

Well, thank goodness we don’t live in a society where cops can beat up/kill minorities with impunity, or I’d be REALLY FREAKING DEPRESSED AND ANGRY after watching this episode.

Probably one of the best Star Trek episodes there is, in my opinion.

I do understand that things are better, especially in terms of what is technically legally allowed, but in others it seems we’ve made frustratingly little progress.

The preacher was totally hilarious. Actually, it’s getting to the point where I can’t say certain parts of the Creed without thinking of wormhole aliens…

I didn’t really like the 4th wall thing – honestly, it’s even more depressing if you float the idea that none of it really exists and it’s all in Benny’s head. In order to be hopeful, you have to believe Sisko’s universe actually happened.

On a superficial note – Martok was the only person I couldn’t ID. Dukat I got right away (something about the way Marc Alaimo cocks his head), as well as Weyoun (he purses his lips in a certain way when he speaks). And of course the main cast, but that goes without saying.

Odo really is kind of a fascist, isn’t he ;)

Possibly the very best episode of Trek in any incarnation. The acting is just superb (with Brooks’ somewhat over the top breakdown scene noted). If I have even the slightest quibble, it’s that the magazines didn’t have staff writers and if Benny Russel was on staff, why would they then pay him 3 cents a word.

Of course, there’s also the extra joke with Hunter and Eaton. Not only are they analogues of real-life married writers Moore and Kuttner, but are being played by a married (at the time) couple.

I vaguely remember when Far Beyond the Stars was scheduled to be broadcast for the first time there was some publicity (without spoilers) about various actors appearing without makeup and one advertisement said Andrew Robinson was going to be one of them. I was disappointed when he didn’r actually appear in this episode.

Not just one of my favorite episodes of Star Trek, but probably one of my favorite episodes of any TV show.

A couple of years ago I was volunteering at a convention and got to spend the whole weekend at Nichelle Nichols’ table. It was amazing to watch one person after another come up to her and tell her how important she had been in their lives.

Other thoughts after reading the post more in depth:

– I did not catch that the Kira/Bashir based writers were married

-O’Brien/Macklin’s robot obsession was really quite funny.

-I’m aware that the characters aren’t necessarily meant to be perfect analogues of their DS9 counterparts, but I do think it’s kind of amusing that Rossoff was accused of communism. The resistance to authority (and butting heads with Pabst/Odo certainly paralells though).

-I think CLB above me expresses a little better why I find the end ‘this might not even exist’ ending to be so unsatisfying. What’s the point, then?

-I thought the comment about the African American writers Russel mentions to be writing for ‘liberal intellecutals’ was interesting, as I tend to think of speculative fiction as a more progressive genre that attracts more liberal/intellecutal types (although there is certainly a variation among such beliefs among authors and fans). But there was an article (I think posted via Tor) recently about how at some conventions where the age gap is considerable, the more aging fandom is still kind of suck in their view of what they wanted the future to be like back in the 50s, which at the time was more reactionary.

When you look at NuTrek and compare it to this, it shows just how many steps backwards NuTrek has taken. Lets not forget how timorous Trek has been on LGBT issues either. Best they’ve managed was one faux-lesbian kiss with Dax (made okay because she used to be male when the relationship started) and a minor handful of offhand comments. When it came to LGBT issues Trek has trailed everything else by a considerable margin. I bet when it eventually comes back to tv we don’t get a Gay or Trans* captain either. So lets not be too congratulatory here.

As far as Far Beyond The Stars Goes. Great drama, interesting Science Fiction concept, crap Star Trek. It would have benefited from being its own tv-movie rather than being folded into a Trek episode.

Besides the clever concept and the powerful social commentary, one thing I love about this episode is how most of the 50s characters are totally opposite to their DS9 counterparts: Benny/Sisko is timid and shy, Herbert/Quark is a socialist with a strong sense of morality, Douglas/Odo is a spineless sycophant, Jimmy/Jake is a cynical, streetwise petty criminal, Willie/Worf is a smooth-talking Casanova, Darlene/Jadzia is a ditzy secretary, and so on… And yet the whole cast makes their little vignettes work, so it doesn’t just feel like were watching the DS9 crew perform a masquerade.

@5

Agreed, and while I enjoyed this story in and of itself, it seemed a little too pat-on-the-back happy for DS9. Avery’s breakdown as noted was overplayed even to me that doesn’t usually notice many acting flaws.

Maybe a 7 or an 8 for me, but falls short of the all-time greats of Trek.

@12: Virtually all the Trek movies are shallower than the TV series. It’s not about old vs. new, just about the richer, deeper storytelling of TV vs. the more superficial storytelling of modern action movies.

I’d just like to jump in on the defense of Russell’s breakdown at the end. Brooks’s acting is understandably theatrical, but there is also a very, very real desperation being voiced by his final lines: “I created it, and it’s real.”

To me, it’s always read as a bit of a meta-textual plea, a response to people who say, “It’s just a silly sci-fi show,” coming from the mouth of one of the people for whom the show and its real-world effects are most important. Russell is living in a world in which Star Trek isn’t given the chance to reach an audience. He’s living in a world in which Nichelle Nichols and Walter Koenig and George Takei are inconsequential. It never really mattered to me whether, within the narrative, Russell’s universe or Sisko’s universe were the “real” one, because regardless of the answer to that question Sisko’s reality exists the same way that Uhura’s and Sulu’s and Chekhov’s and Guinan’s and Janeway’s realities exist. They exist for the audience, and they’re REAL. To me, the desperation appears overacted only at first, but actually plays true. He’s channeling half a century’s worth of desperation from the people who only even want to be in the same room as Nichelle Nichols, just so they can see for themselves that Uhura is REAL.

In all the times I’ve rewatched this, I never caught that Kay and Jules were supposed to be married.

I think I’ll stick my neck out for Avery Brooks here too–I know it’s come up earlier in this rewatch that some people think his portrayel of strong emotions is too much, but I always just thought it as his particular style and I kind of like it sometimes. After all, in real life, people respond to things in different ways. And I’ve never actually witnessed anyone having a total mental breakdown, but I would think that in that case, turning the energy up to 10 could make sense. I would be more worried about people underplaying that scene. I think his portrayel helps to sell that this guy is going totally bonkers while at the same time strongly selling his speech to everyone.

The thing I can’t stand is the breaking of the fourth wall at the end. I get the analogy that Trek is supposed to have the message and vision that Benny Russell had, but it’s just too much. Obviously it’s all a made up tv show, but I want to believe it’s real within the context of it’s own universe. I think where I didn’t mind Trek breaking the 4th wall was in “Ship in a Bottle” where they say maybe they are all playing on a box on someone’s table, because it’s a realistic joke to make and it serves to fuel the bigger joke of Barclay testing to see if he’s still in the holodeck.

One of my favorite eps though.

Apart from the great story, I really like the novelty of seeing the actors without their alien makeup. Odd hearing their voices come out of those hue-MON faces.

Oh, and Armin Shimerman totally reminds me of Frank Gorshin in this episode (that is, when he’s in serious mode and not crazily laughing mode). But from everything I’ve heard about Harlan Ellison, I can totally see the connection there.

@16: Which, again, underlines my problem with the episode. It works fantastically on a metatextual level, as musing and commentary by the show’s writers — but doesn’t make much sense on a textual level, as an event that took place within the Trek universe.

What I was surprised to discover not long ago is that there are people out there who believe that Benny Russell and these other characters actually existed in the 1950s of the Trek universe. Which doesn’t make sense to me, since they’re clearly variations on the people in Sisko’s life, with similar names, relationships, roles, and the like. I suppose it could be argued that what Sisko experienced was a blending of his own life and that of the “real” Benny, that the people wouldn’t have looked like Sisko’s crewmates and family and enemies if he’d checked the historical records. But it’s always seemed more likely to me that the whole scenario was fabricated, probably drawn from Sisko’s own knowledge of the history of the period.

Although… then again… we had no prior indication that Sisko had an interest in that period, and even if he did, he probably wouldn’t have known all the details of the lives of science fiction writers in 1950s New York City. So I suppose it’s possible that whoever created the visions, whether the Prophets (for some very unclear reason) or the Pah-wraiths (in an attempt to dishearten Sisko or undermine his sanity), drew on details from Earth’s actual past. So I suppose it is possible that the characters and events in the vision were based at least partly on reality, though the names and other specifics may have been changed to fit the needs of the vision. Heck, maybe they “really” were based on Delany and Asimov and Ellison and Kuttner and Moore and Campbell and Mays.

Still, that’s just part of why it feels so artificial as a Trek story, so much of an authorial intrusion, however powerful and brilliantly done. Creating a whole alternate life for Sisko in such detail, and making him unsure whether his reality is just someone else’s story, seems like a hell of a Rube-Goldbergian way for either the Prophets or the Pah-wraiths to try to influence him.

I really don’t want to sound like a troll but this episode is … plain and ordinary. The charme of a fantastic series and especially of Star Trek comes from the power of allegory. Human realities are cleverly mirrored in strange and unusual surroundings. Alien cultures or customs reflect on human cultures, high concept sci fi ideas trigger philosophical qustions.

Here we have a noble black man in the 50s who is oppressed plus all the cliches accompanying this picture. A young black man who gets on the wrong track of life due to surroundings, hoodlum cops and so on. We’ve seen that often enough and what’s the point of having it on Star Trek?

Keith correctly points out that the series rarely even talks about its multi-racial cast because it’s normal for the characters. And that is Star Trek’s utopian appeal: pretending that it’s the most normal thing on earth. Whining about the oppression is artistically and mentally a step back. You’d never think Sulu couldn’t handle the Enterprise because not even the slightest doubts ever arise about that and nobody would even dream of suggesting some race inferiority regarding his abilities. He just is the pilot. That’s creating positive role models.

I’m writing this also because as Star Trek fan one tends to dismiss sci fi elements like anomalies, time travel and so on and praise simple human stories. However the crucial factor for the prominence of a sci fi series is teh sci fi. The competition on the market for simple human stories is pretty stiff and includes lots of the whole world literature and film. While (well done) sci fi on the other hand is more unique.

All told I strongly oppose Avery Brooks attempts to transform the series into a Civil Rights movement propaganda especially his later utterance in an episode with Vic Fontaine when he is referring to a “hard time for OUR people” which is absolutely annoying.

Star Trek has tackled racism in some interesting ways, I love the much maligned Let That be Your Last Battlefield for the simple allegoric twist it’s based on which immediately collapses all racism based on appearances. Far Beyond The Stars is just pat, self-congratulatory Political Correctness.

Along the lines of @21, I was never big on Sisko’s out-of-place emphasis on Black history. He says to Jake on several occassions in the series that essentially they can’t forget their history. What history? The Civil Rights movement was 400+ years before. That would be like modern day Englishmen talking about the English Civil War or modern day Spanish folks bringing up the inquistion. Certainly some events (The Holocaust for example) have a long effect on society, although honestly The Holocaust is not even 100 years old. Will we cite it as often as an historic examples of things in 2100? 2200? Would non-white individuals in the 24th century really be that well versed and concerned with 1950s/1960s Black US history?

The whole point of much of the discussion here is that in the 24th century, no one bats an eye at a captain/pilot/crewmember who is female or a person of color. Maybe it has to do with Sisko’s specific background. His father lives in New Orleans, which is semmingly still partly Cajun/Creole (whichever fits better with his restaurant) and a place with a lot of African American influences. Of course, then the question becomes “why is Joseph Sisko still influenced by a 350+ year old movement?” That could go on ad nauseum to the present, without a definitive line on where the obvious/spoken influence of the 50s/60s would mostly fade.

I do recall in Enterprise, there was a bit of xenophobia (toward aliens races from an otherwise fairly united Earth, though that was largely in response to an attack on the planet. Otherwise, the racial tensions were allegedly long solved (Picard speechifies this a few times in TNG).

This is my all-time favorite episode of Star Trek, any series. Great review, and thanks for the kind words about my story.

I loved this episode. Loved. It. If either the writing was bad or the acting wasn’t right, it would have come across as preachy and shallow. Both were spot on and instead created an episode that was nuanced and meaningful. It was a great tribute to the writers who, in their own way, helped bring about a brighter future. It’s not perfect (and never will be), but reminding us where we’ve been helps keep us moving forward.

I didn’t mind the bit at the end with Sisko seemingly wondering who’s real, him or Benny, maybe because I didn’t see it as breaking the fourth wall. To me it was just a sign of how real the visions were for Sisko, and that the effects will still be there later.

#22

You mentioned the Holocaust. I’m pretty sure modern Jews are familiar with the story of Moses and the Hebrew slaves. It’s not outside the realm of believability to see the future Siskos, who are still technically African American (New Orleans, right?), being familiar with their nation’s past.

@21: While I can see where you might feel that this episode is beating people over the head too much, and where I might even agree that the progess of Trek is that it doesn’t hang a lampshade on the minority characters but rather just accepts them as normal, I think that an episode like this can go a long way to pointing out that “Hey, we’re not in the 24th century yet.” It’s a reminder that not everyone is a Star Trek fan and takes these things for granted. Racism still exists. In a way, setting it in an actual Earth past is an allegory…just as the message here was that Benny had a dream of a better future, Star Trek is meant to be a dream of a better future that is as relevant today as it was in 1966 (I think they made that abundantly clear with the breaking of the fourth wall at the end).

Even today, we still live in a world where cops can shoot minorities and get away with it. We live in a world where, as it has been mentioned, minorities are cast as sidekicks and rarely as leads–directly analagous to Benny’s plights with his stories. So I think sometimes it’s nice to be reminded that Star Trek really is still the dream, and we have to work to make it reality rather than just watch it and accept it as truth.

And I doubt that anyone who’s struggled with prejudice or oppression (be it racially motivated or otherwise) would consider calling attention to the prejudice “whining.”

The history of brutal racism against African Americans on the North American continent is right around 400 years and counting right now. Doubtless that history will continue for at least another few generations beyond this point. I don’t find it remotely unbelievable that Sisko would value the lessons that what by his time will have been five or so centuries of recorded racial brutality brought to the utopian world he lives in. The “present” time in the Star Trek universe isn’t so improved on our own as it is because anybody has forgotten this history.

@20:

Thanks for your thoughtful response. I apologize this one won’t have the same time or effort put into it. I guess what I’m saying is that for me, in this case, the metatextual quality of the episode is good enough to transcend the text. And in a certain way, I also think that may be the point of the whole thing. Though I hate to say I’m not finding myself able to adequately explain that last thought this second.

@27 – Thanks for making my point to @22 for me. It’s not about the Civil Rights movement necessarily. That is just a recent past (to us) movement, but it’s not like it came out of nowhere. It came from hundreds of years worth of oppression. It’s not like it’s over yet either.

One more episode that proves DS9 has retained its edge even now.

I’m going to provide a dissenting opinion here, but one of a different sort.

Up-front: This episode was beautiful. Beautifully-acted (especially from Avery Brooks, who has never not impressed me in this series), well-directed, a treat to watch from beginning to end, and meaningful. It surprised me how willing it was to tackle racism head-on like that, and I would recommend it as one of the better pieces of TV I’ve ever watched.

That said, the controversial part: I don’t feel like this was a good episode of Deep Space Nine.

It’s entirely possible that there is something tying it in later on, but having only the context of ‘every episode before it’, this episode feels like a complete nonsequitur. There is nothing to really presage its coming, nothing to really explain it other than ‘Sisko is stressed over the loss of a good friend’, it resolves itself without intervention or explanation, and so far it doesn’t actually seem to have affected anything.

This episode really just feels like ‘we wanted to make an episode of Not Deep Space Nine, so we kind of shoehorned it into the show’. If I am wrong on the facts, please correct me, because I want to like this not just as ‘a thing I watched’ but also as ‘an ep of DS9’; but as it stands, I can’t really give it the latter.

The era picked was a good one. It predates the ugliness of Civil Rights unrest (not to mention the antiwar movement) of the 1960s and 1970s, but postdates things like a woman’s right to vote, the integration of the armed forces, and the integration of sports. It’s an era where progress is evident, but it hasn’t progressed nearly far enough.

It’s also significant for where things happen. I like (for certain values of the word “like,” of course, given what it is) that the story is set in New York; there’s a bit of a fog that ends up getting cast in discussions of the Civil Rights era. Poll taxes, segregated water fountains…the mythology/hagiography of the era can make the problem look exclusive to southern states. And it wasn’t–the North may not have had Jim Crow, but that didn’t mean it was harmony and perfection.

Seeing all the actors of of makeup in this episode was pretty weird. I didn’t even recognise Michael Dorn until his second appearance in the episode, and I didn’t realise JG Hertzler’s role ’til I read this rewatch.

Lots of things have already been said about this episode, in this comments thread alone, and I’m not much qualified to add to them. But I’ll say that I’m conflicted about it. I agree that it’s a bit strange as a Trek episode, being way out of context in the setting and ongoing storyline at least, but it’s one of the trekkiest episodes in it’s ethos.

My only nit to pick with this episode is that the Bashir in Rapture was a changeling because they had already switched to the new uniforms and had not rescued Bashir from the prison camp. Sure, it’s a minor thing, but once I realized it I can’t un-know it.

Otherwise, an absolutely incredible episode.

Bobby

Wonderful episode, wonderful review. I can understand the criticisms raised here and can’t deny their force. But the strength of the story just overwhelms those things for me.

@13, about all the characters playing slightly opposite some key characteristics of their DS9 selves…as a contrast, I like that O’Brien is still basically O’Brien. Just like the Mirror O’Brien is also still basically O’Brien.

On the question of historical memory, I think people are seriously overestimating the distance of history. The Reformation was almost five centuries ago and still has enormous implications in the daily lives of many people. The Sunni/Shia split was far earlier and still matters. The mass extermination and colonization of the New World is almost entirely distant from the lives of most people who now live in this country and yet it still lingers as a specter. Which isn’t to say it’s placed front and center, but that’s exactly the point.

I very much believe that someone like Sisko would be very concerned in remembering the suffering inflicting in the name of racial order. As an introspective man, and as a defender of the Federation–even as it dips into unsavory practices–he also surely would be concerned about the terrible elements of our history re-emerging.

Surpassing the mistakes of our past can’t just mean locking them up in a box and pretending that those impulses no longer pose any threat. That’s precisely what allows them to re-emerge. That was the whole Q arc in TNG, wasn’t it?

How much do I love this ep? From it’s allegory, to the constant nature of its message. My geek “affiliations” tend to be comics, videogames and written SF, so when Pabst made his comment about what readers wanted, along with his unthinking assumptions as to who his readers were… maaaan. It simply does not change, does it?

You can also see how much fun some of the writers must have had, in making the characters “like them”.

Does it lack some subtlety? Sure, but some anvils need to be dropped. Repeatedly.

First off, count me in as one of those inspired by this episode. I can still feel the goosebumps as I recall Benny’s anguished cry, but “It was real!” It felt like vindication after years of growing up getting picked on for liking a nerdy sci-fi show or having the actor playing your hero convincingly make the point on national TV that you “need to get a life.”

My baby boy is 19 months old. When he gets old enough, I plan to share Star Trek with him. This will be one of the first episodes we watch together.

——–

I agree with folks here who say that this felt shoehorned into the bugger storyline. I realize that DS9 was the first incarnation of Star Trek to introduce serialized storytelling in a massive way, but I’m curious why they couldn’t have just had a bottle show with no real connection to the Dominion War plot.

The West Wing did something like this with the episode “Isaac and Ishmael.” It was the first episode to air after 9/11 and was a bottle show that they used to talk about the Middle East and “why they hate us.” As I recall, it was introduced by the cast in the beginning, and they made the point that the story was deliberately “outside our normal continuity.”

It makes you wonder why they couldn’t have done the same thing on Star Trek.

Crunching the numbers.

Things that didn’t add up for me in this episode.

Firstly, Benny says he is being paid 3 cents per word (this would mean he was a freelance writer).

Assuming he wrote a short story of 5,000 words, thats $150. The median income of a male in 1950 USA was $2,570 (according to Wikipedia). That’s almost $50 per week. The average black american male was paid almost half at $1,471.

So he gets about three weeks pay for a short story. Then he gets fired by the publisher, which would imply he was on a wage or salary. So is he a freelance writer or paid by the hour ?

Next, why would a publisher order the pulping of an issue ?

My understanding of the relationship is that the editor has creative control of a magazine or newpaper and the publisher owns the businnes. Surely he would would sack the editor before pulping an issue. It would be an economic disaster. And how many issues would there be ?. At the time, Galaxy way selling for $0.35. For a magazine of about 50,000 words that’s $1,500 to pay for the writing alone. To re-coup that cost you would need to sell over 4,000 issues. How much is that – a stack 40 metres high or 400kg – assuming each is centermetre thick and 100g. You’re not going to carry that into the office !

Don’t believe it !

And BTW – Did americans _really_ have that accent in the 1950s. Surely it’s a regional accent rather than specific to that time.

Seeing the writers here bat around the idea of how to make the story work with an African-American hero makes me think that perhaps something similarly happening with the Kirk and Uhura kiss? The idea that won out is that they were under alien mind control.

@22: You say it’s unbelievable that Sisko would be knowledgeable about or affected by centuries-old African-American history. Do you have the same objection to McCoy’s affectations of being an old-school Southerner, or Chekov’s devotion to Russian history, or Bashir and O’Brien’s endless fascination with the Alamo and the Battle of Britain? Or, for that matter, Worf’s reverence toward Kahless, or Spock’s toward Surak? What is so unusual or unbelievable about a character being knowledgeable about his cultural heritage?

@28: Oh, I agree completely about the metatextual quality transcending the text. The metatextual stuff makes it a brilliant and powerful episode. I’m just disappointed that the text makes so little sense in-universe.

@30: Yes, you’ve pinpointed just what my problem is. It’s a fantastic piece of television and a powerful social commentary, but it doesn’t quite fit into DS9. I mean, allegorically and thematically it’s a perfect fit for Star Trek, and the emphasis is a perfect fit for DS9 since DS9 was the first SF show with an African-American lead (that I know of). But it doesn’t grow organically out of the narrative of the series. It feels more like the rules of the series were arbitrarily changed to allow this story to be a part of it. It feels like an intrusion, albeit a welcome one — like if a meteorite of solid gold crashed into the middle of your living room. It’s an extraordinary find in and of itself, but it doesn’t quite fit the context.

@32: I’m surprised that anyone could fail to recognize Michael Dorn the moment he speaks. That voice is unmistakeable no matter how much his face changes. Hertzler’s voice is pretty unmistakeable too.

@35: You’re so right. Sometimes the powers that be don’t understand who their audience is. Like all the comic publishers and animation executives today who believe the audience for superheroes is 100 percent male, even though it’s really about half female. They’re unthinkingly alienating a huge segment of their audience, and that can only hurt their profits.

@37: What accent do you mean?

NigelBaker: there were several accents on display in the episode, but most of them were New York accents which, as a New Yorker myself, I can say were generally accurate. Aron Eisenberg, Marc Alaimo, Terry Farrell, and Jeffrey Combs in particular had strong versions of NYC accents (Farrell’s was more Brooklyn, Eisenberg’s more Bronx, Alaimo and Combs more Manhattan).

—Keith R.A. DeCandido, Noo Yawka

Also thanks to everyone for the kind words about this rewatch entry. This episode has been written about so much that I was initially frozen and intimidated and had no idea what to say. And then I started writing, and the whole thing kind of jumped out and wrote itself down, winding up being the second-longest of my DS9 rewatches (after “The Way of the Warrior”).

—Keith R.A. DeCandido

What I think is great about this episode is all of the reactionary commentary it generates. I enjoyed the episode for its technical and gimmicky aspects, the cute in-jokes, seeing the actors play essentially another crew but with different personalities and sans makeup, the acting. But it also feels very after-school special-y to me, like a “very special episode of Deep Space Nine.” To me it just seems like the lesson is racism (and sexism) are bad, m’kay and here it’s presented too sledge-hammery.

@36

Well, Isaac and Ishmael is a dreadful episode so I wouldn’t really take that as a good example. Being freed from the burdens of continuity tends to make people a heck of a lot preachier and destroys characterization.

I think this episode would work fine as simply a random side-effect of Sisko’s previous illness. Not caused or inspired by anyone. And the story is then about where his mind goes when it’s trying to repair itself, and the way that the crushing necessities of his life at this point manifest allegorically for him in this landscape.

History lessons often focus on what is important to the society doing the teaching. To a society as enlightened and inclusive as the Federation, therefore, teaching about less enlightened and inclusive times would be considered a priority to show how these changes came about. So I would think that the civil rights movement would be taught as standard in Earth schools in the 24th century. And any good history lecturer knows that it isn’t just the big events themselves that are important to teach, but the conditions which led up to those events occurring. So I have no problem at all with the idea that Sisko would be very well versed in the prevailing attitudes of the era.

Furthermore, the idea that 500 years is too long for people to still be concerned with past injustice is ridiculous. Every Jewish person is well versed with the events that took place at Masada, and still feels the injustice of them. That was 2,000 years ago.

This episode certainly has problems, but I also think it certainly transcends them. I will admit that, if I were the show runner and my writers had pitched the idea of an issue episode about racism where all the actors played totally different characters in 1950’s New York, I’d have told them to go away and write me something where they have to recalibrate the sensor array instead. It sounds like a terrible idea, but it works fantastically well. I could nitpick faults, but I don’t see the point when the end result is so exhilarating.

(Regarding the over-the-top nature of Benny’s breakdown, incidentally, this is why I never think it is a good idea for an actor to direct himself. There’s nobody to tell him “you know what….”)

@40 I did appreciate the variety of “New York” accents as good attention to detail on the part of the actors. In 1953, those accents would probably have been even more evident and distinctive than they are now, so it really added to the ambiance of the period scenes.

There is an Arthur C Clarke short story that ends with the line,”If any of you are still white, we can cure you.” Anyone know the title, and when and where it was originally published?

An excellent write up of this episode complete with sobering reminder that ethnic minority leads are still vanishing rare in TV. Certainly British television can’t maintain any superior airs over here.

I do think it needs to be emphasised once again that Star Trek in all its incarnations was never a simple SF series about adventures in future space and was never designed or intended to be an attempt to show a plausible or potentially accurate vision of the 23rd and 24th centuries. It’s a truism, I know, but the majority of SF, especially on TV, is about the present day. Remember that the only reason Roddenberry originally decided upon that genre was his frustration at the difficulties of discussing contemporary issues in contemporary based stories. Closer to our present, only the rebooted Battlestar Galatica could tell a story featuring suicide bombers who are portrayed heroically. Fretting about how it fits into the season arc seems to be missing the point, possibly to avoid dealing with the issues raised.

This episode remains a salutory and saddening reminder of how little we have progressed and how far we still need to go. It becomes too easy for us fans to fall into the ‘we can watch a series about humans who no longer suffer or endure or tolerate discrimination, aren’t we the good guys’ and not actually do anything in thought, word or deed to combat actual discrimination around us. That’s why the uncertainty at the end is so poignant. If we fail to do anything, Benny Russell’s dream along with Gene Roddenberry’s will remain just that. Dreams.

@40: But haven’t New York accents evolved over time? I’ve recently been listening to some old-time radio series from the ’40s and ’50s that were made by New Yorkers, and the actors and announcers in those shows seemed to have a common accent that was more New England-ish, less rhotic, than what I hear from the New Yorkers I know today.

Hard to say anything about this episode that hasn’t already been said. Beautifully done on every level. To me, this is DS9’s The Inner Light. Not only with a similar plot, but also an unfliching look into a what might have been situation for Sisko.

One of Ira’s and Hans’ masterpieces, superbly brought to life by Avery.

It’s also a bold statement on just how much writers have fought and bled to become respected and integrated. I sympathize with everyone inside that room. Where else but in sci-fi could you challenge the conservative standings of modern society and push new, fresh ideas at that point? I like to think Gene would have been proud of this one.

I particularly adore Shimerman as Rossoff. He’s as invested in the role of the outspoken liberal writer, and manages to create an equally intense polar opposite to the Snyder character from Buffy.

I used to question the use of 20th Century racial conflict through the viewpoint of a 24th Century character, but since Benny isn’t really Benjamin, it works. This is how it’s done, unlike Sisko’s fourth-wall breaking rant regarding racial prejudice on Badda-Bing Badda-Bang.

Also, thanks to Avery’s breakdown theatrics on this one, and Vreenak’s performance on the upcoming In the Pale Moonlight, this episode became a major part of a long-running internet meme:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6lHgbbM9pu4

@39 and @44: I probably didn’t present it well, and that is my fault. My issue (and it’s not even a big issue, I enjoyed the episode very much) is not that cultural heritage is known, so much, as there is still such monolithic cultural heritage. I understand it is not as though New Orleans and France and Ireland (or some form of them) didn’t still exist at this point, but I guess I would figure that over 400 years, culture would have really changed. The idea that almost everyone is a purely French or Irish or Japanese or American person after years of (frequent?) racial mixing and technological advances enabling faster/better transportation and travel (more cultural mixing) seems almost too simple.

I am reminded of the South Park episode about immigrants from the future, who are all the same generic, similar looking people of a middling color. The notion is that after generations of mixing, the melting pot melts into one. Obviously, that is an exaggeration in 4000 years let alone 400 years; however, I guess I just figured there should be less “I’m Irish so I act like 1900s Irish people” and more “I’m Irish and given 400 years of additional history, the Ireland I grew up in has multiple more modern influences, though I do know the history of my nation and my ancestors.”

I think this episode of DS9 can be compared to an episode of DS9’s archrival series, Babylon 5: “Passing through Gethsemane”. Both are stand alone episodes with great scripts, but don’t seem to fit that much in the story arcs. Both also can be shown to people that know nothing about the shows and they will enjoy it.

I absolutely love this episode. Even Avery Brooks’s very emotional performance during the breakdown works for me. I echo above-voiced concerns that it’s hard to really think it “works” for this story to really happen on DS9, but it’s good enough that I forgive that. (Though, honestly, I could do without it having been revisited next season, and then seemingly ad nauseum in the books.)

This is a rare episode of modern Star Trek that truly sets out to important, and it succeeds in spades.

-Andy

@48:

It’s possible what you’re hearing is the Mid-Atlantic accent.

This isn’t one of my very favorite episodes, but I’m glad it’s there. For its deeper messages, its change of pace, its excellent acting, and the surreal way that it doesn’t really fit into the continuity as a whole — reminds us that even in the 24th century some things are still a mystery.

Picking out the actors when they looked different was an interesting exercise. I don’t think I ever caught Aron Eisenburg. Others, I think I mostly recognized by voice rather than facial features (if they normally wear masks).

Although the characters are supposed to somewhat be contrasts to their actors’ usual roles’ personalities, it still cracks me up to see Rossoff react so angrily to being called a “Communist,” knowing how much of an insult that would be to a Ferengi too. :)

I don’t think I ever batted an eye over having a black captain. I think when I first heard about a new Trek series and was told, “The captain is black,” I said something like, “Cool, so what’s it actually *about*?” With that in mind … it saddens me to realize that, as KRAD points out, genre fiction has followed DS9’s lead so poorly on this issue. I’d love to see more well-acted leads of other races! Television producers, take note!

I live in a part of the country where minorities aren’t likely to get harassed by the police, but now I’m left wondering — even in places like this, how many of my friends are still part of the reason that minorities can’t be the leaders in a story?!

@53: But why would so many radio actors be using the mid-Atlantic accent to play American characters? The main show I’ve been listening to is The Adventures of Superman, whose characters were mostly from Metropolis, supposedly a major American city. (Generally treated as a surrogate New York, although in the earliest comics it owed more to Jerry Siegel’s hometown of Cleveland, Ohio. I daresay the NY-based radio series probably did a lot to influence its NY-ish portrayal.)

@54: Sliders had an African-American lead actor in its final season, though that was because he was the only original cast member left after the three original white leads had left. But in the final season, half the regular cast was black.

Sleepy Hollow has an African-American co-lead in Nicole Beharie. She’s second-billed after Tom Mison, but she’s an equal lead in every sense (and is so commanding and powerful a presence she makes Sisko seem like a milquetoast), and there’s plenty of diversity in the overall cast. The CW remake of Beauty and the Beast also has a fantastically diverse cast, with Kristin Kreuk in the lead (and finally getting to play a Chinese-American character rather than passing for white) and with three of the five second-season regulars being nonwhite (up from three out of six in season one). Then we just had Extant with Halle Berry as the lead, though it was a pretty bad show.

In animation, we’ve got The Legend of Korra, set in a universe where all the characters are Asian, Inuit, or other nonwhite (and nonblack) ethnicities; but most of the actual voice actors are white.

Upcoming we’ve got Marvel’s Luke Cage series on Netflix. There’s also an adaptation coming up of Neil Gaiman’s American Gods, and developer Bryan Fuller has made it clear he’s not going to cast a white actor as the mixed-race lead character.

On the other hand, we still get problematical cases like The 100, where the majority of the black or Asian characters got progressively killed off — including one of the lead characters of the source novel!

So we are making progress, getting more diversity in TV. But it’s still an uphill climb.

@@@@@ 46, StrongDreams

The story you are asking about is “Reunion” dated November, 1963. I don’t know where it was first published, but you can find it in the short story collection The Wind From The Sun.

On to other things. If anyone needs something in universe to suggest a reason for Sisko’s strong interest in, and knowledge of, the subject, they should look to the third season’s “Past Tense.” Sure, that happened well into the next century, but the foundation of all the wrongs that led to the Bell Riots had been set long before the mid 1950s. After having walked in Gabriel Bell’s shoes, Sisko would have studied that history, and he would have made the connection to the earlier Civil Rights struggles even if it wasn’t already being taught in Earth grade school history classes at that time.

In the Cards is also a bottle episode, so it’s not like DS9 had grown beyond having them.

I’ve made this comment in various re-watches before now, and I’m sure I’ll be making it again in the future. People judging shows from the 60s, 70s and 80s against today’s ideas and complaining about how they did (or did not) treat gays, religious minorities, non-believers, or the Civil Rights movement have to keep in mind the realities of the times in which the shows were produced. TNG, and DS9 were syndicated and that meant the producers (You could say they were represented by Douglas Pabst in this episode.) had to walk a fine line between the kind of stories the creative staff wanted to tell, and the kind of ideas that the powers in control of the subscriber stations could not, or just would not, accept. Everyone thinks of the major television landmarks, like Roots, and asks ‘why didn’t they do more?’ They were trying to do more. Not everything could be packaged in a mega-hit that fell into place in such a way that it could not be turned down. Most of the advances have been small steps. For example, WKRP took on censorship in an episode where a potential big-money advertiser presented the list of songs that could not be played. If you are having trouble remembering it, think of the discussion over the John Lennon song “Imagine.”

My last point is a bit of trivia. While the space station in the story drawing resembles Deep Space Nine, it is based on (modified from) a wheel space station design seen in Chesley Bonestell’s paintings for the Collier’s Man In Space series and available as a model kit from Lindbergh since the late 50s or early 60s.

@55:

Because a lot of the ‘userbase’ for the Mid-Atlantic was in the northeast US, and it was especially used in theater, radio, and other media productions. It’s really common to run into it in recorded media up through the late 50s to early 60s, as I understand it.

@56 That is a terrific point about “Past Tense.” I had sort of forgotten about that. After essentially being Gabriel Bell, he would have had a different viewpoint than maybe the average 24th century ancestorally “black” individual, who may not have the explicit (or even implicit) knowledge.

One of the bigger problems with much of Star Trek (especially TNG) is the way that the big stuff that goes down this week has little to no impact the next week. Everyone gets sick, almost dies, dozens of nobodies die in a random skirmish, and yet the next week everyone is going around like normal. Of course DS9 really fixed that (most of the time) with the serialized nature of the story arcs like the war and the politics of Ferenginar and of Klingons. Still, I often forget to take earlier episodes into account when analyzing the actions of characters later, precisely because it often wasn’t worthwhile before DS9.

@56: You may have a point about inclusion as far as TNG goes; at the time, including a gay character would’ve been rather controversial. It was certainly controversial when DS9 did “Rejoined” and the same-sex kiss. But by the time VGR and ENT were around, gay characters on TV had become far more visible and common. There was no excuse for continuing to leave them out of Trek.

BOTH the evil cops had Irish surnames, so a little stereotyping still seems to be okay…

@60: Actually, back then, the police departments of many major cities really were overwhelmingly made up of Irish-Americans. According to this article, by 1900 nearly 70% of the NYPD was Irish by birth or parentage. Apparently, according to TV Tropes, there was a wave of Irish immigration in the later 19th century that corresponded to the establishment of professional police departments in many major US cities, and since police officer was a low-paying, low-skill job at the time, it was the kind of job that would tend to go to recent immigrants. The NYPD was still over 40% Irish by the mid-’60s. That’s why you come across so many Irish cops in the media of the era, like Chief O’Hara in the ’66 Batman.

So since this was set in New York City in the 1950s, it’s entirely reasonable that the majority of police officers, good or bad, would’ve been Irish.

Thanks for the lovely analysis of this particular DS9 episode. I’d pegged the Rosoff character as being a PK Dick stand-in, but at that height and level of argumentativeness, Ellison’s an even better bet. Also, thanks for providing the provenance of the Hugo on Rosoff’s desk: I’d assumed it was the 1968 trophy for “City on the Edge of Forever,” but the 1968, 1974 & 1977 Hugo bases are remarkably similar.

@61 yes, but still, having two negative characters in a television show belonging to the same ethnic group can reinforce a stereotype. This would be the same regardless of the ethnic group portrayed. It can be the result of just not thinking about the implications, but, nevertheless, can still make viewing uncomfortable for members of that group.

P.S. Long time reader, first time commenter on this site. My local channel is showing this season at the moment, so the reading the reviews is really enhancing my enjoyment.

@63: I just don’t see the grounds for complaining about a historically accurate portrayal. It’s not as if they were speaking in exaggerated brogues and saying “Begorrah” and “Sweet Mother Machree.” They spoke in Manhattan accents, as Keith says, and neither of their names was ever spoken on camera except for Ryan addressing Mulkahey as “Kevin” at one point. I never even realized they were supposed to be Irish until you brought it up. So how is it a stereotype? It’s just a bit of background texture, not even noticeable within the episode.

One of my favorite episodes.

@64 Here in England, our television is SO careful in how certain ethnic groups are portrayed because we have had some really shocking portrayals in the past. Historical accuracy is often ignored because many people wouldn’t understand that aspect and just see a link between the ethnicity of a character and his/her behaviour. As someone in space once said: “It is not logical, but it is true.”

Anyway, I don’t want to belabour this point and you’ve given me a nice discussion, so thanks.

@66: We’ve had plenty of shocking portrayals of many ethnic groups ourselves. But like I said, there’s nothing at all in the actual episode that’s “ethnic” about the characters, since their surnames come only from the script. They’re the perpetrators of discrimination, not its victims.

I know Avery Brooks sometimes has a tendency to overact, but if ever there’s a time to overact it’s when your character is having a mental breakdown. I don’t think Benny’s breakdown was overdone at all. Sometimes that’s what they’re like.

@12 – It was pointed out to me by someone with experience in these matters that while it wasn’t intentional on the part of the writers, it’s very easy to parse Dax as a trans woman. And not just because she’s tall, has a strong chin and starts half her stories with “when I was a man.”

Krad, I just wanted tell you how much I appreciated your thoughtful, beautiful summary of this great, great episode. As an African-American, I was grateful the writers did this episode; even if it didn’t fit into the overall narrative of the series, it still gave wonderful food for thought, which Star Trek at its best has always done.

I doubt anyone’s going to be reading still at this point in time, but I do want to share a personal story about this episode.

First of all, of course, I loved this episode.

When my wife Nomi and I were at the Worldcon after this episode aired (Bucconeer, 1998), we discovered that co-writer Marc Scott Zicree was on a panel we were interested in. After the panel, we approached him to tell him how much we had enjoyed the episode. We thought that would be it, but he found us outside the panel within the next hour, and invited us to join him for lunch. That started a friendship which has lasted to this day.

Anyway, I just wanted to share that.

Also, I like robots. They’re very efficient.

— Michael A. Burstein